This series, developed over the course of a five year period, encompasses four interconnected projects created while I was living in New York. During this time, my day job in architecture began to merge with a personal search for inner peace through practices like ayahuasca ceremonies and transcendental meditation. These experiences profoundly influenced the work, which is characterized by repetitive, dreamlike architectural imagery and a subtly surreal atmosphere. Sculptural elements woven throughout the series draw from construction materials and building environments, reflecting both my professional surroundings and a deeper meditation on structure—both physical and psychological. Together, these works form a meditation on transformation, tension, and the quiet intersections between the built world and the inner one.

- TitleA Nervous System

- Type(s)

- Agenda

- Year(s)2011–2017

- LocationNew York

Roaring in Silence, 2013-2016

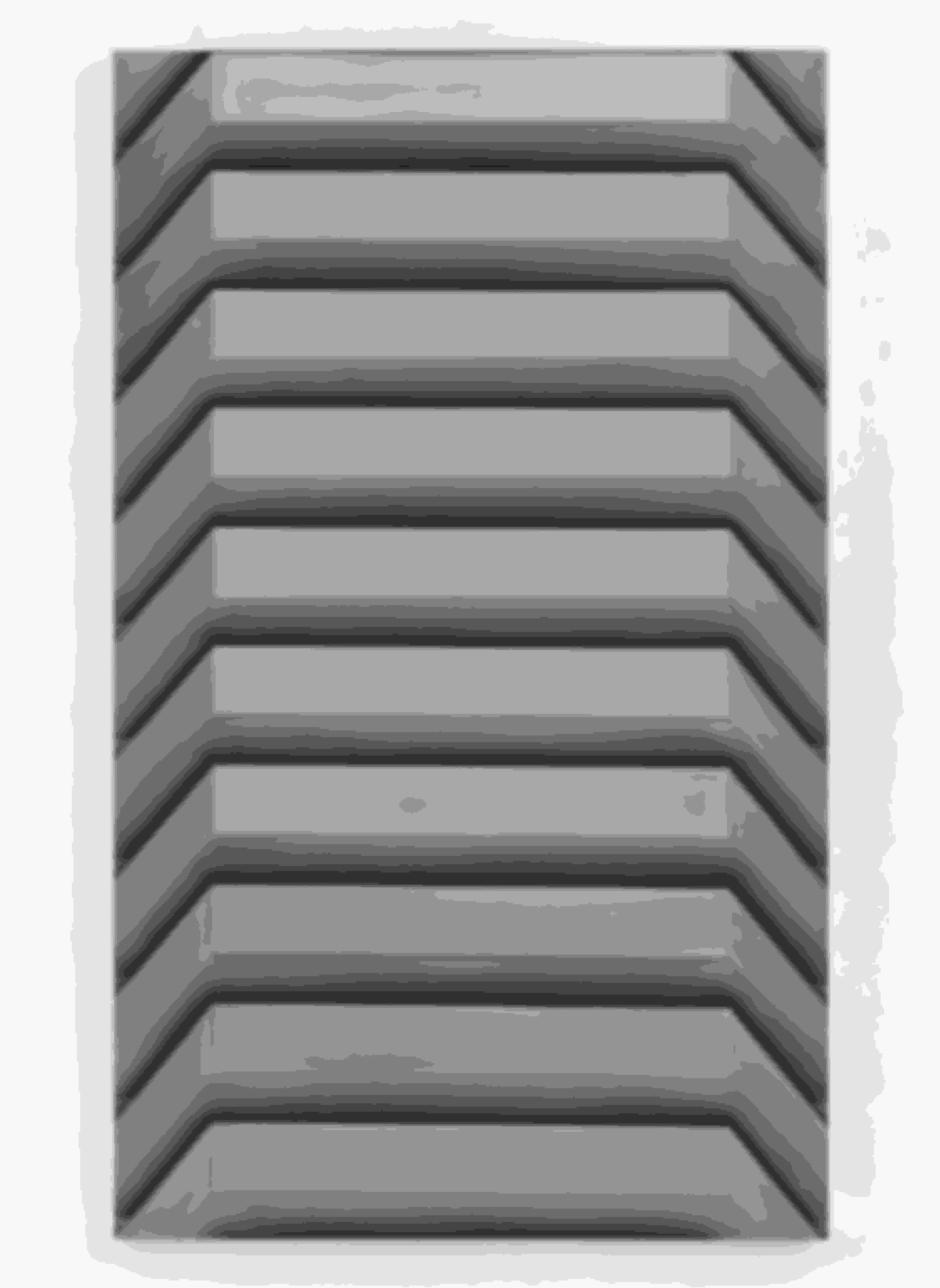

A hall meanders to and fro, monotonous and maze-like. Monolithic, a series of stacked rhomboid shapes recedes downwards and away from the painted surface. The wall opens upon a void.

I began this series of paintings after I started meditating, reflecting upon the way that this practice prompted me to explore my own mind as one would an architecture. These placeless sites, structureless constructs are meditative objects of focus, puzzles for the mind to traverse and search. Their shapes are simultaneously alien and familiar—they tease the brain with their push and pull. These canvases suggest the variability of my experiences even within my own mind. In some, through focusing on iterative shapes that expand ever outwards, I transcend conscious thought. The articulated planes of a home, rendered roofless and flat, are exploded by the possibility of what lies beyond. By contrast, other compositions suggest a feeling of entrapment or claustrophobia, which impel me to realize the illusory limits I place upon my own consciousness.

In some forms of meditation, a mantra is repeated until the speaker is no longer sure where the sound begins or ends. I imagine that these labyrinthine canvases exude a deafening silence, a solitary roar. Dams, radiators, and drivers are forms that regulate current and change of speed. A signal is divided, distributing itself into smaller cavities. An echo—thought—repeats, reverberates, and fades.

The Home

and are paintings that explore the concept of home and reference the famous Italian artist and writer Giorgio de Chirico. Since I was young I was interested with the concept of home. If you look through my art during the past 12 years there are numerous projects about the home.

Title: De Chirico's Doorbell

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Title: Without a Roof

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Scarpa

is inspired by the artist and architect Carlo Scarpa. Strange to think Scarpa died falling down a staircase in Japan. His name ‘Scarpa’ means shoe, and he made the most beautiful staircases ever. Sometimes the universe likes to make strange coincidences. He died on something he also became loved for.

Title: Scarpa's Stairs

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Dams, Radiators, and Drivers

Dams, radiators, and drivers are forms that regulate current and change of speed. A signal is divided, distributing itself into smaller cavities. An echo—thought—repeats, reverberates, and fades. Three paintings: Dams, Radiators, and Drivers.

Title: Dams

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Title: Radiators

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Title: Drivers

Medium: Oil on Canvas

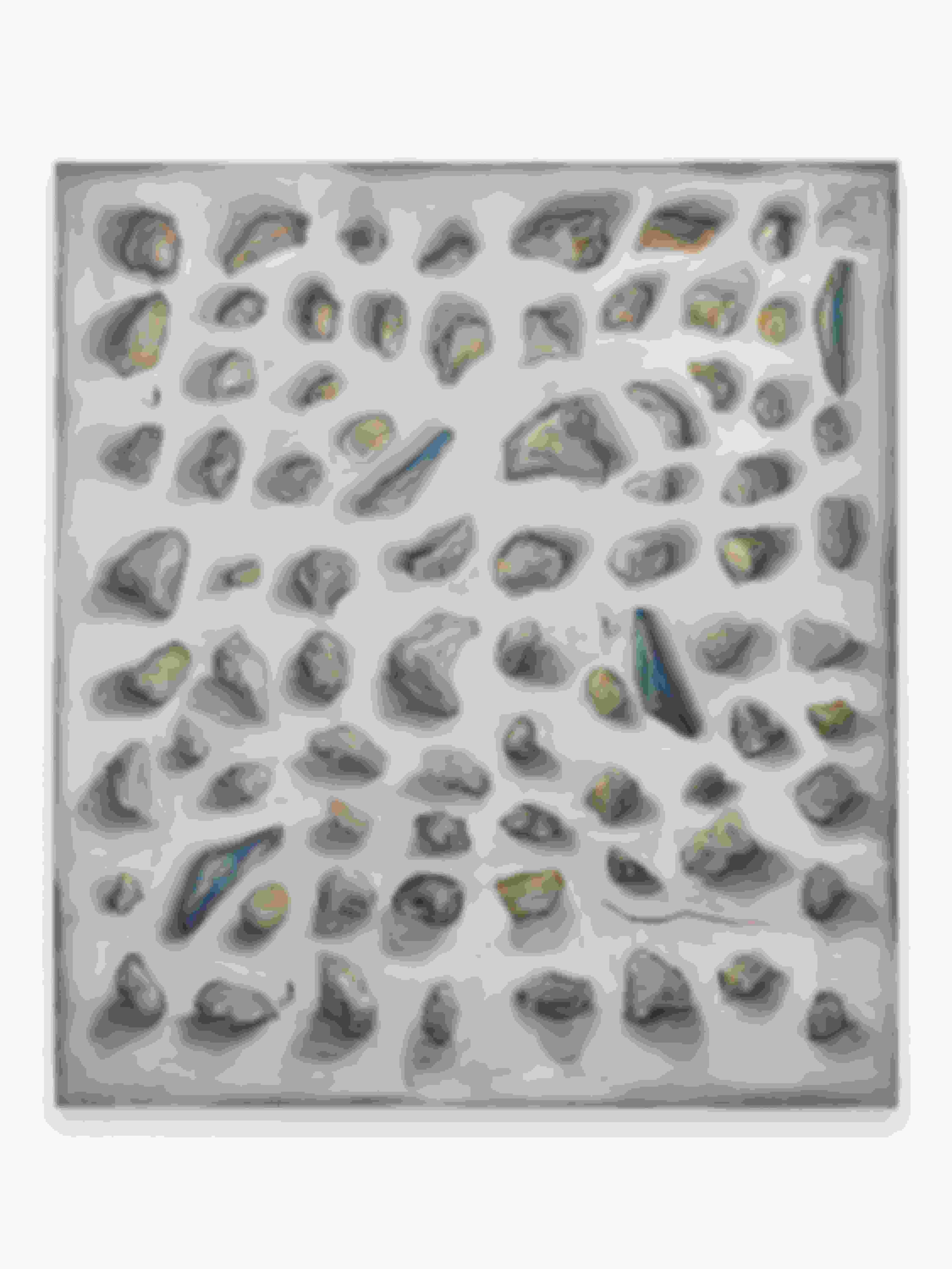

Stones and Window Lock

and reference the concept of the internal mind and the maze it can play on ourselves.

Title: Window Lock

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Title: Beach Stones

Medium: Oil on Canvas

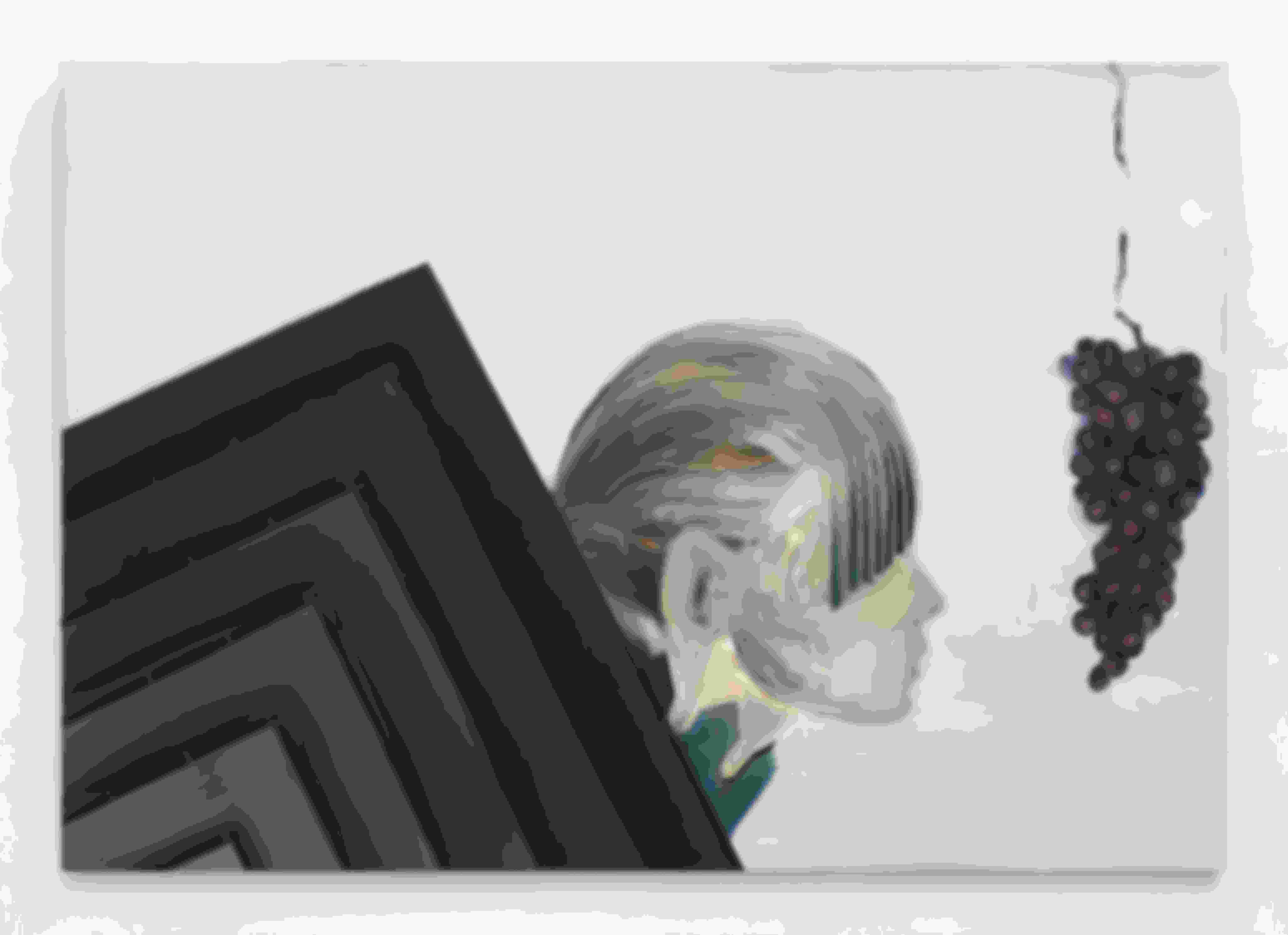

Hypnosis

These paintings were made while researching , an effort of trying to understand how to control the mind.

Title: Girl with the Grapes

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Title: Take One Step Further into the Unknown

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Title: Spiral Inwards

Medium: Oil on Canvas

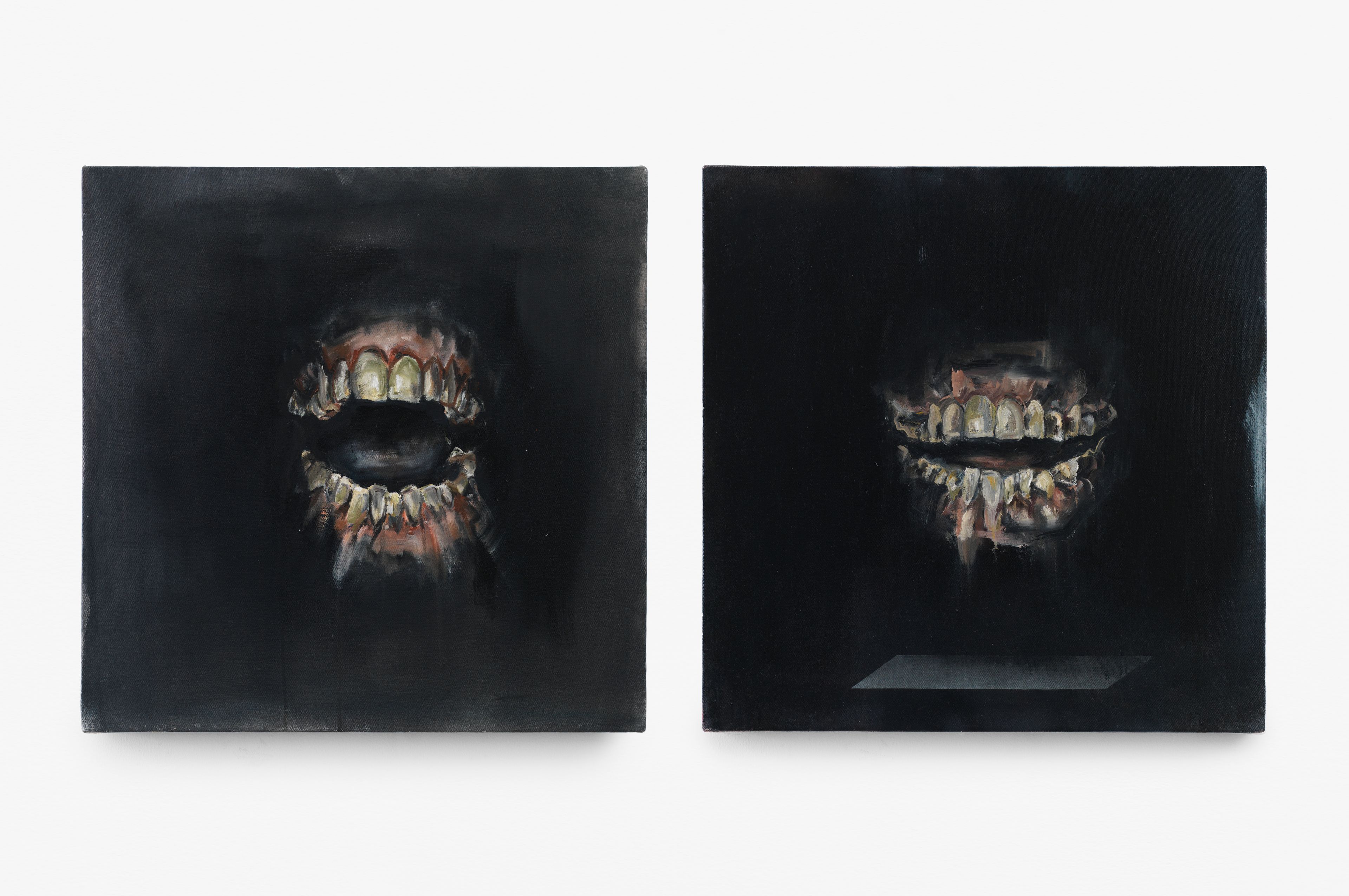

Teeth and Bones

Our Visible Skeleton and A Stone for a Tooth and Chicken with no Head and Feet were all inspired by the desire to feel the rawness of life. Still dealing with grief from Grey Period, I continuely pushed myself to feel the essence of life. Looking at the works of helped me feel the silent screams.

Title: Our Visible Skeleton

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Title: A Stone for a Tooth

Medium: Oil on Canvas and Stone

Title: Chicken with no Head and Feet

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Anechoic Chamber

This work was inspired by my visit to the at the Venice Biennale. The experience was overwhelming and inspired two works: and .

Title: Infinite Silence of Paris

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Title: Womb Reflection

Medium: Oil on Canvas

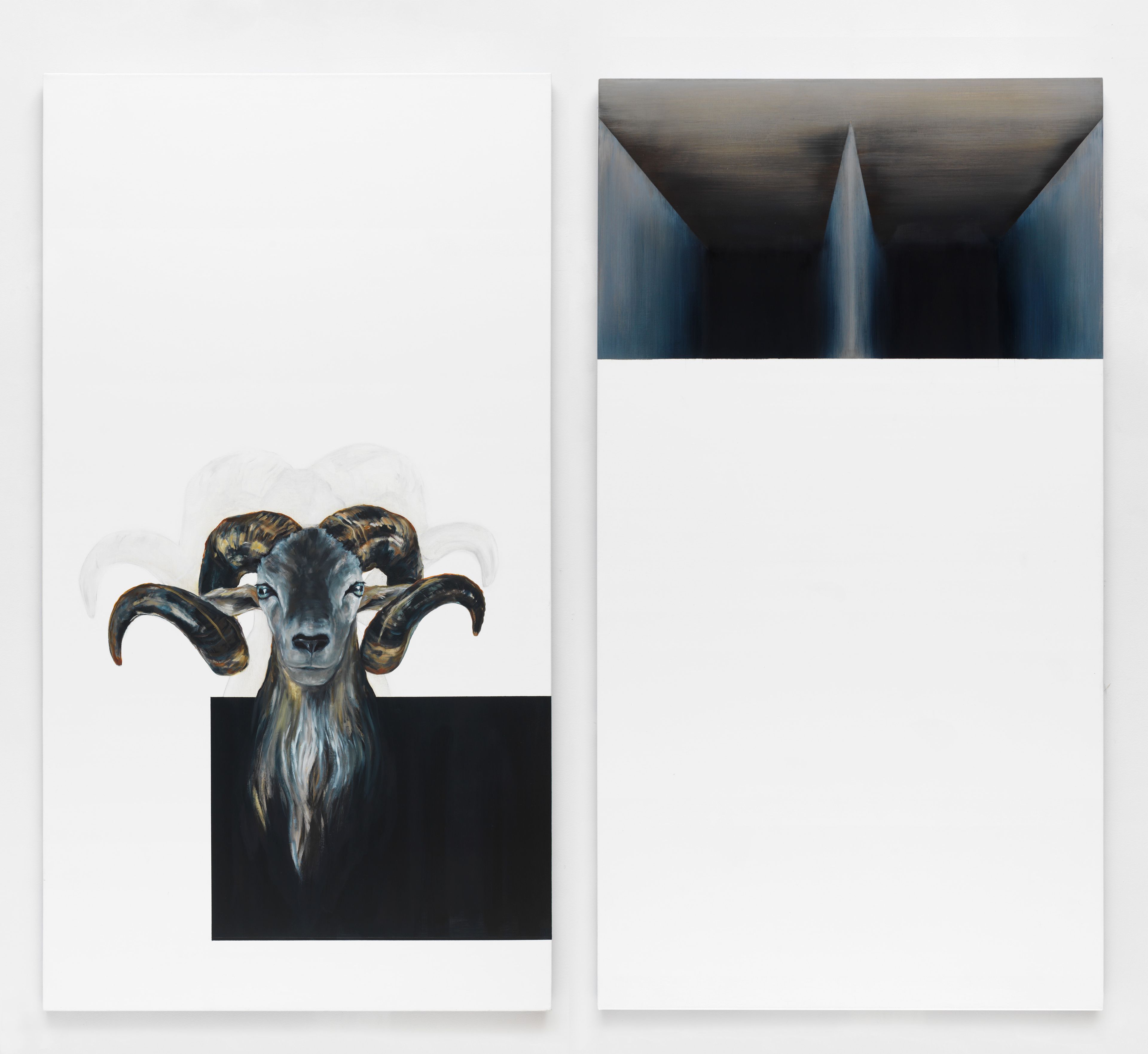

Ram of Breganze

I saw a ram during my last visit in Italy. The way this large animal stared at me in the forest, I had no form of protection either, it was something I haven't experienced before. “Throughout Greek culture, the ram figures prominently as a metaphor of strength and courage (thus the association with Ares).”

Title: Ram of Breganze

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Spider from a Scar

Why did I paint an oyster? Was it my love for oysters? Perhaps. Many times I would . The sort of the belly button of the oyster … where the mollusk and the shell united. That blackness was like a . I could get lost starring inside the depth of it.

Title: Spider from a Scar

Medium: Oil and Dust on Board

Meditation Pavilion

Peering at Faint Lights, 2015

“Ayahuasca” is a hispanicization of a Quechan term—a language spoken by the indigenous peoples of the South American Andes. The word concatenates two others:“aya,” meaning “spirit,” “soul,” or “corpse”; and “waska,” meaning “vine.” Vine of the soul. Made from Banisteriopsis caapi vine and Psychotria viridis shrub, ayahuasca is a psychoactive brew that has been used in spiritual ceremonies indigenous to South America for as long as 1,000 years.

The last two years that I spent in New York, I participated in the MFA program at Columbia University. In my early months there, I had trouble choosing subjects to paint. I was also beginning to battle physical symptoms from overexposure to toxins in oils and mineral spirits. I had trouble breathing and felt that I was destroying my body every time I picked up a paintbrush. Painting had been part of my life since my late teens—and I began to fear that I would have to give it up.

Moving Walls

Reminiscing of Being Inside the Womb

Being Pulled up to the Sky by my Jawbone

Installation concept

Entering the Void

Journal entry:

I stood in a tunnel of moving color, a well of intertwined yellows and oranges, forming intricately interconnected lines and shapes. Slowly, these faded out to reveal an infinite nothingness at the center of my vision. Pedestals bearing alien forms, the distorted features of unknown creatures, emerged from the floor of that void. I felt my body drop, swallowed by cold dirt walls as I plunged into the depths of the earth. In that unlit center, the same alien faces appeared in patterned grids of colored light as though guiding me through space. I traversed a landscape of mazes, monochrome and oppressive. I felt my body continue its descent to the roots of the world, to the roots of the plants that ayahuasca is made from. But I wasn’t afraid at that moment. I was in a place that had always been, one that I was meant to find in due time. In front of me was a rounded space, like a little cave or grotto with an iron gate, upon which perched a snake, partially enmeshed in the wrought iron. Behind this barrier was a plane of black earth, starred here and there by white teeth emerging from the compacted soil. As I looked closer, I saw rows of skulls lining the black, clay walls.

In the midst of this death and darkness, my eye lit upon a floating, luminous form, glowing an energetic red. A womb. Suddenly, I felt that I could remember what it was like to be inside my mother’s body, those long months before I took my first breath.

I turned away and was confronted by another cave, its mouth open and seeming to beckon. Inside, a figure sat at a leaden desk. A second chair was placed across from him, but I didn’t want to sit. As I looked closer, I saw that the man’s face was concealed. I felt suddenly claustrophobic, terrified not by the looming cavern walls but rather by this austere male presence.

I looked about and found a further grotto, a black void abuzz with energy that seemed to draw my body inside. I knew, without knowing how, that I would die if I entered that void. I was afraid.

In another vision, I saw into the time that follows death. From inside of a mausoleum wall, I watched coffins stacking in a morbid game of Tetris. Through the concrete of the mausoleum wall and the wood of the coffin, I saw that my own body was in one of those boxes.

I floated up and away, suddenly detached from my body, as though someone had grabbed the underside of my jaw and lifted my head into the skies. My body dangled, but I felt nothing, only a slight pressure in my jaw. I saw forests, rolling countryside. I saw my body becoming one with the hills of Bassano. I arrived in an empty white space, void of people or things. I called out, and I was with my grandparents. I called out again, and some members of my family were there. Together, in that place, we were all made of light—somewhere below, my body was only a vessel, a shell. For the first time, I understood myself as a vitality in a human form, a presence that transcends material. I was no longer afraid of death.

Icaros

https://youtu.be/2K8SXPt7F5w?si=GnmjoLdorQLKsX3D

Blood Feather of a Northern Flicker, 2016

In the fall of 2016, my body began to fall apart. I was suffering from heavy metal toxicity, adrenal fatigue, burnout, respiratory problems, muscle weakness, and brain fog. I felt as though I couldn't move, my legs weighing me down like twisted steel. Even reading was an effort—I would scan the same paragraph over and again without once being able to turn the lines on the page into meaning or sound. Slowly, I tried to cleanse my body with different regimens, all while drinking water solely from glass bottles to avoid all risk of contaminants.

On my way to the studio one morning, I found a northern flicker that couldn’t fly and could barely walk. I took the bird to a nearby animal hospital, where she died a few days later. I felt that the bird was me, mirroring my own body’s sharp decline.

Later, I found myself looking at the feather she left in the box that I used to transport her. The shaft of the feather was filled with blood, still in the process of growing when it fell out prematurely. Over the course of my own recovery, I thought often of the northern flicker, which became—in my mind—a symbol for my own unruly body.

For the five years before my symptoms began, I had lived in a Brooklyn loft—slightly sketchy, not up to code, definitely illegal. Though I have never been able to confirm it, I have wondered whether the pipes in that building were what prompted my own physical decline. Often invisible behind the walls of a building, water pipes and electricity cables are like the lifeblood of a building. When the body of my home became contaminated, so too did I.

Extending the metaphor that links my physical self to the structures that hold me, this collection is assembled from architectural fragments, including corroded water pipes, alabaster remnants, and the twisted remains of structural I-beams. I bound these ruined materials together with wire or roller-chain, a material which—like my body—bent one direction, flows beautifully, and the other, torques and can be put under severe duress.

Materials

Blue wax, copper plates, copper pipes, copper wire, drywall, nails, roller-chain, steel I-beam, oil on canvas, Bonotto fabric on canvas, feather, alabaster stone, radiator

Copper Nail and the Swallow, 2017

Hammer a copper nail into a sapling, and the tree will die. It takes more nails to fell an older tree, to infiltrate the growth cells and interrupt the photosynthetic process with oxidized copper toxins—but it can be done. Copper was one of the earliest metals known to man, first coming into use between 8,000 and 10,000 B.C.E. as a substitute for stone in the production of ornaments, weapons, and tools. The discovery that it could be alloyed with tin to produce bronze spurred an age of expanded trade and cultural development across Europe and Asia Minor that lasted from 3300 to 1200 B.C.E. The metal’s current name was given by the Romans, who called it “aes Cyprium,” Latin for “Cypriate copper”—where the Romans primarily mined the metal—and latter abbreviated to “cuprum.” Its material value to the Romans and the cultures that would follow is evident in the fact that few Roman bronze sculptures or architectural constructions survive, most melted down and recycled for use in warfare and industry.

The dome of the Roman Pantheon, for example, was originally covered by copper and bronze plates that were respectively stolen and repurposed by Constans II in A.D. 663 and by Pope Urban VIII in the 17th century. Today, copper is still used widely in construction, electronics, and transportation, valued for its malleability, durability, and conductivity. And it is still wielded, on occasion, in the killing of trees.

This body of work looks at humankind’s relationship to nature through the lens of copper, weaving a web of material confusions that demonstrate our growing alienation from the earth. A coppery tree, composed of rusted-out disc rotors mounted on a steel pipe, seems to grow from a square of sheet metal. Beside it, twisted rods and angles spring from stone like an angular bush.

On another plane of metal, piled upon a slab of asphalt (almost mistakable for a third type of rock), two desert stones are levered at an infinitesimal angle by a copper nail, which splits them as though puncturing the wood of a petrified stump. One stone is from Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest exporter of crude oil, and the other from Arizona, which holds one of the major copper deposits in the United States.

Behind these assemblages, an engulfing painting recedes illusionistically into iterative coffers—an image of Harry Weese’s plan for the ceiling of the Washington, D.C. Metro system, which was itself adapted from the ceiling of the Pantheon. Stone, metal, and paint come together in an illusion of nature that is too geometric, too well designed.

Several of these materials refer to forms of infrastructure that, while fueling trade and cultural exchange from the Bronze Age to the present, have contributed to the destruction of the environment. Copper is one of the primary materials that enables the United States’s love affair with the automobile industry.

Running on Saudi oil and assembled from copper tubing and parts, cars travel the landscape on rivers of asphalt. However, copper’s use in computing and electronics also beckons a possible future, in which electric cars replace oil motors. At the installation’s periphery, chunks of asphalt are suspended by metal wire like the weighty pendulums of unseen clocks, suggesting alternatives of adaptation or annihilation and the necessity of addressing the climate crisis.